DirectX

| DirectX A component of Microsoft Windows |

|

|---|---|

| Details | |

| Included with | Windows 95 OSR2 Windows NT 4.0 and all subsequent releases |

Microsoft DirectX is a collection of application programming interfaces (APIs) for handling tasks related to multimedia, especially game programming and video, on Microsoft platforms. Originally, the names of these APIs all began with Direct, such as Direct3D, DirectDraw, DirectMusic, DirectPlay, DirectSound, and so forth. The name DirectX was coined as shorthand term for all of these APIs (the X standing in for the particular API names) and soon became the name of the collection. When Microsoft later set out to develop a gaming console, the X was used as the basis of the name Xbox to indicate that the console was based on DirectX technology.[1] The X initial has been carried forward in the naming of APIs designed for the Xbox such as XInput and the Cross-platform Audio Creation Tool (XACT), while the DirectX pattern has been continued for Windows APIs such as Direct2D and DirectWrite.

Direct3D (the 3D graphics API within DirectX) is widely used in the development of video games for Microsoft Windows, Microsoft Xbox, and Microsoft Xbox 360. Direct3D is also used by other software applications for visualization and graphics tasks such as CAD/CAM engineering. As Direct3D is the most widely publicized component of DirectX, it is common to see the names "DirectX" and "Direct3D" used interchangeably.

The DirectX software development kit (SDK) consists of runtime libraries in redistributable binary form, along with accompanying documentation and headers for use in coding. Originally, the runtimes were only installed by games or explicitly by the user. Windows 95 did not launch with DirectX, but DirectX was included with Windows 95 OEM Service Release 2.[2] Windows 98 and Windows NT 4.0 both shipped with DirectX, as has every version of Windows released since. The SDK is available as a free download. While the runtimes are proprietary, closed-source software, source code is provided for most of the SDK samples.

Direct3D 9Ex, Direct3D 10 and Direct3D 11 are only available for Windows Vista and Windows 7 because each of these new versions was built to depend upon the new Windows Display Driver Model that was introduced for Windows Vista. The new Vista/WDDM graphics architecture includes a new video memory manager that supports virtualizing graphics hardware to multiple applications and services such as the Desktop Window Manager.

Contents |

History

Windows 95 and DirectX 1.0

In late 1994 Microsoft was on the verge of releasing its next operating system, Windows 95. The main factor that would determine the value consumers would place on their new operating system very much rested on what programs would be able to run on it. Three Microsoft employees – Craig Eisler, Alex St. John, and Eric Engstrom – were concerned because programmers tended to see Microsoft's previous operating system, MS-DOS, as a better platform for game programming, meaning few games would be developed for Windows 95 and the operating system would not be as much of a success.

DOS allowed direct access to video cards, keyboards, mice, sound devices, and all other parts of the system, while Windows 95, with its protected memory model, restricted access to all of these, working on a much more standardized model. Microsoft needed a way that would let programmers get what they wanted, and they needed it quickly; the operating system was only months away from being released. Eisler (development lead), St. John, and Engstrom (program manager) worked together to fix this problem, with a solution that they eventually named DirectX.

The first version of DirectX was released in September 1995 as the Windows Games SDK. It was the Win32 replacement for the DCI[3] and WinG APIs for Windows 3.1. Simply put, DirectX allowed all versions of Microsoft Windows, starting with Windows 95, to incorporate high-performance multimedia. Eisler wrote about the frenzy to build DirectX 1 through 5 in his blog.[4]

DirectX 2.0 became a component of Windows itself with the releases of Windows 95 OSR2 and Windows NT 4.0 in mid-1996. As Windows 95 was itself still new and few games had been released for it, Microsoft engaged in heavy promotion of DirectX to developers who were generally distrustful of Microsoft's ability to build a gaming platform in Windows. Alex St. John, working as an evangelist for DirectX, staged an elaborate event at the 1996 Computer Game Developers Conference which game developer Jay Barnson described as a Roman theme, including real lions, togas, and something resembling an indoor carnival.[5] It was at this event that Microsoft first introduced Direct3D and DirectPlay, and demonstrated multi-player MechWarrior 2 being played over the Internet.

The DirectX team faced the challenging task of testing each DirectX release against an array of hardware and software. A variety of different graphics cards, audio cards, motherboards, CPUs, input devices, games, and other multimedia applications were tested with each beta and final release. The DirectX team also built and distributed tests that allowed the hardware industry to confirm that new hardware designs and driver releases would be compatible with DirectX.

Prior to DirectX, Microsoft had included OpenGL on their Windows NT platform. At the time, OpenGL required "high-end" hardware and was focused on engineering and CAD uses. Direct3D was intended to be a lightweight partner to OpenGL, focused on game use. As 3D gaming grew, OpenGL evolved to include better support for programming techniques for interactive multimedia applications like games, giving developers choice between using OpenGL or Direct3D as the 3D graphics API for their applications. At that point a "battle" began between supporters of the cross-platform OpenGL and the Windows-only Direct3D. Incidentally, OpenGL was supported at Microsoft by the DirectX team. If a developer chose to use OpenGL 3D graphics API, the other APIs of DirectX are often combined with OpenGL in computer games because OpenGL does not include all of DirectX's functionality (such as sound or joystick support).

In a console-specific version, DirectX was used as a basis for Microsoft's Xbox and Xbox 360 console API. The API was developed jointly between Microsoft and Nvidia, who developed the custom graphics hardware used by the original Xbox. The Xbox API is similar to DirectX version 8.1, but is non-updateable like other console technologies. The Xbox was code named DirectXbox, but this was shortened to Xbox for its commercial name.[6]

In 2002 Microsoft released DirectX 9 with support for the use of much longer shader programs than before with pixel and vertex shader version 2.0. Microsoft has continued to update the DirectX suite since then, introducing shader model 3.0 in DirectX 9.0c, released in August 2004.

As of April 2005, DirectShow was removed from DirectX and moved to the Microsoft Platform SDK instead. The DirectX SDK is, however, still required to build the DirectShow samples.[7]

Releases

| DirectX version | Version number | Operating system | Date released |

|---|---|---|---|

| DirectX 1.0 | 4.02.0095 | September 30, 1995 | |

| DirectX 2.0 | Was shipped only with a few 3rd party applications | 1996 | |

| DirectX 2.0a | 4.03.00.1096 | Windows 95 OSR2 and NT 4.0 | June 5, 1996 |

| DirectX 3.0 | 4.04.00.0068 | September 15, 1996 | |

| 4.04.00.0069 | Later package of DirectX 3.0 included Direct3D 4.04.00.0069 | 1996 | |

| DirectX 3.0a | 4.04.00.0070 | Windows NT 4.0 SP3 (and above) last supported version of DirectX for Windows NT 4.0 |

December 1996 |

| DirectX 3.0b | 4.04.00.0070 | This was a very minor update to 3.0a that fixed a cosmetic problem with the Japanese version of Windows 95 | December 1996 |

| DirectX 4.0 | Never launched | ||

| DirectX 5.0 | 4.05.00.0155 (RC55) | Available as a beta for Windows 2000 that would install on Windows NT 4.0 | July 16, 1997 |

| DirectX 5.2 | 4.05.01.1600 (RC00) | DirectX 5.2 release for Windows 95 | May 5, 1998 |

| 4.05.01.1998 (RC0) | Windows 98 exclusive | June 25, 1998 | |

| DirectX 6.0 | 4.06.00.0318 (RC3) | Windows CE as implemented on Dreamcast | August 7, 1998 |

| DirectX 6.1 | 4.06.02.0436 (RC0) | February 3, 1999 | |

| DirectX 6.1a | 4.06.03.0518 (RC0) | Windows 98 SE exclusive | May 5, 1999 |

| DirectX 7.0 | 4.07.00.0700 (RC1) | September 22, 1999 | |

| 4.07.00.0700 | Windows 2000 | February 17, 2000 | |

| DirectX 7.0a | 4.07.00.0716 (RC0) | March 8, 2000 | |

| 4.07.00.0716 (RC1) | 2000 | ||

| DirectX 7.1 | 4.07.01.3000 (RC1) | Windows Me exclusive | September 14, 2000 |

| DirectX 8.0 | 4.08.00.0400 (RC10) | November 12, 2000 | |

| DirectX 8.0a | 4.08.00.0400 (RC14) | Last supported version for Windows 95 | February 5, 2001 |

| DirectX 8.1 | 4.08.01.0810 | Windows XP, Windows Server 2003 and Xbox exclusive | October 25, 2001 |

| 4.08.01.0881 (RC7) | This version is for the down level operating systems (Windows 98, Windows Me and Windows 2000) |

November 8, 2001 | |

| DirectX 8.1a | 4.08.01.0901 (RC?) | This release includes an update to Direct3D (D3d8.dll) | 2002 |

| DirectX 8.1b | 4.08.01.0901 (RC7) | This update includes a fix to DirectShow on Windows 2000 (Quartz.dll) | June 25, 2002 |

| DirectX 8.2 | 4.08.02.0134 (RC0) | Same as the DirectX 8.1b but includes DirectPlay 8.2 | 2002 |

| DirectX 9.0 | 4.09.00.0900 (RC4) | December 19, 2002 | |

| DirectX 9.0a | 4.09.00.0901 (RC6) | March 26, 2003 | |

| DirectX 9.0b | 4.09.00.0902 (RC2) | August 13, 2003 | |

| DirectX 9.0c[8] | 4.09.00.0903 | Service Pack 2 for Windows XP exclusive | |

| 4.09.00.0904 (RC0) | August 4, 2004 | ||

| 4.09.00.0904 | Windows XP SP2, Windows Server 2003 SP1, Windows Server 2003 R2 and Xbox 360 | August 6, 2004 | |

| 4.09.00.0904 | Windows XP SP3 | April 21, 2008 | |

| DirectX - bimonthly updates[9] | 4.09.00.0904 (RC0 for DX 9.0c) | The February 9, 2005 release is the first 64-bit capable build.[10]The last build for Windows 98/Me is the redistributable from December 13, 2006.[11] The last build for Windows 2000 is the redistributable from February 5, 2010.[12]. April 2006 is the first official support to Windows Vista[13] and August 2009 is the first official support to Windows 7 and DX11 update[14] | Released bimonthly from October 2004 to August 2007, and quarterly thereafter; Latest version: June 2010[15] |

| DirectX 10 | 6.00.6000.16386 | Windows Vista exclusive | November 30, 2006 |

| 6.00.6001.18000 | Service Pack 1 for Windows Vista, Windows Server 2008 includes Direct3D 10.1 |

February 4, 2008 | |

| 6.00.6002.18005 | Service Pack 2 for Windows Vista, Windows Server 2008 includes Direct3D 10.1 |

April 28, 2009 | |

| DirectX 11 | 6.01.7600.16385 | Windows 7, Windows Server 2008 R2 | October 22, 2009 |

| 7.00.6002.18107 | Windows Vista SP2 and Windows Server 2008 SP2, through the Platform Update for Windows Vista and Windows Server 2008[16] | October 27, 2009 |

- Notes

- DirectX 4 was never released. Raymond Chen explained in his book, The Old New Thing, that after DirectX 3 was released, Microsoft began developing versions 4 and 5 at the same time. Version 4 was to be a shorter-term release with small features, whereas version 5 would be a more substantial release. The lack of interest from game developers in the features slated for DirectX 4 resulted in it being shelved, and the corpus of documents that already distinguished the two new versions resulted in Microsoft choosing to not re-use version 4 to describe features intended for version 5.[17]

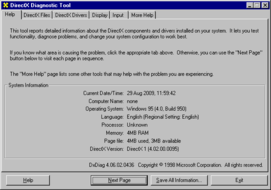

- The version number as reported by Microsoft's DxDiag tool (version 4.09.0000.0900 and higher) use the x.xx.xxxx.xxxx format for version numbers. However, the DirectX and Windows XP MSDN page claims that the registry always has in the x.xx.xx.xxxx format. Put another way, when the above table lists a version as '4.09.00.0904' Microsoft's DxDiag tool may have it as '4.09.0000.0904'.[18]

Logos

The logo originally resembled a deformed radiation warning symbol. Controversially, the original name for the DirectX project was the "Manhattan Project", a reference to the US nuclear weapons initiative. Alex St. John, creator of the original Microsoft DirectX specification, claims that the connotation with the ultimate outcome of the Manhattan Project (the nuclear bombing of Japan) is intentional, and that DirectX and its sister project, the Xbox (which shares a similar logo), are meant to displace Japanese videogame makers from their dominance of the industry.[19] However, this meaning is publicly denied by Microsoft, which instead claims that it is merely artistic design.[19]

DirectX 1.0–6.0 |

DirectX 9.0 |

Components

The components of DirectX are

- DirectDraw: for drawing 2D Graphics (raster graphics). Now deprecated (in favor of Direct2D), though still in use by a number of games and as a video renderer in media applications.

- Direct3D (D3D): for drawing 3D graphics.

- DXGI: for enumerating adapters and monitors and managing swap chains for Direct3D 10 and up.

- Direct2D for 2D Graphics

- DirectWrite for Fonts

- DirectCompute for GPU Computing

- DirectInput: for interfacing with input devices including keyboards, mice, joysticks, or other game controllers. Deprecated after version 8 in favor of XInput for Xbox 360 controllers or standard WM INPUT window message processing for keyboard and mouse input.

- DirectPlay: for communication over a local-area or wide-area network. Deprecated after version 8.

- DirectSound: for the playback and recording of waveform sounds.

- DirectSound3D (DS3D): for the playback of 3D sounds.

- DirectMusic: for playback of soundtracks authored in DirectMusic Producer.

- DirectX Media: comprising DirectAnimation for 2D/3D[20] web animation, DirectShow for multimedia playback and streaming media, DirectX Transform for web interactivity, and Direct3D Retained Mode for higher level 3D graphics. DirectShow contains DirectX plugins for audio signal processing and DirectX Video Acceleration for accelerated video playback.

- DirectX Diagnostics (DxDiag): a tool for diagnosing and generating reports on components related to DirectX, such as audio, video, and input drivers.

- DirectX Media Objects: support for streaming objects such as encoders, decoders, and effects.

- DirectSetup: for the installation of DirectX components, and the detection of the current DirectX version.

DirectX functionality is provided in the form of COM-style objects and interfaces. Additionally, while not DirectX components themselves, managed objects have been built on top of some parts of DirectX, such as Managed Direct3D[21] and the XNA graphics library[22] on top of Direct3D 9.

DirectX 10

A major update to DirectX API, DirectX 10 ships with and is only available with Windows Vista and later; previous versions of Windows such as Windows XP are not able to officially run DirectX 10-exclusive applications.[23] There are unofficial ports of DirectX 10 to XP.[24] Changes for DirectX 10 were extensive.

Many former parts of DirectX API were deprecated in the latest DirectX SDK and will be preserved for compatibility only: DirectInput was deprecated in favor of XInput, DirectSound was deprecated in favor of the Cross-platform Audio Creation Tool system (XACT) and lost support for hardware accelerated audio, since Vista audio stack renders sound in software on the CPU. The DirectPlay DPLAY.DLL was also removed and was replaced with dplayx.dll; games that rely on this DLL must duplicate it and rename it to dplay.dll.

In order to achieve backwards compatibility, DirectX in Windows Vista contains several versions of Direct3D:[25]

- Direct3D 9: emulates Direct3D 9 behavior as it was on Windows XP. Details and advantages of Vista's Windows Display Driver Model are hidden from the application if WDDM drivers are installed. This is the only API available if there are only XP graphic drivers (XDDM) installed, after an upgrade to Vista for example.

- Direct3D 9Ex (known internally during Windows Vista development as 9.0L or 9.L): allows full access to the new capabilities of WDDM (if WDDM drivers are installed) while maintaining compatibility for existing Direct3D applications. The Windows Aero user interface relies on D3D 9Ex.

- Direct3D 10: Designed around the new driver model in Windows Vista and featuring a number of improvements to rendering capabilities and flexibility, including Shader Model 4.

Direct3D 10.1 is an incremental update of Direct3D 10.0 which is shipped with, and requires, Windows Vista Service Pack 1.[26] This release mainly sets a few more image quality standards for graphics vendors, while giving developers more control over image quality.[27] It also adds support for parallel cube mapping and requires that the video card supports Shader Model 4.1 or higher and 32-bit floating-point operations. Direct3D 10.1 still fully supports Direct3D 10 hardware, but in order to utilize all of the new features, updated hardware is required.[28]

DirectX 11

Microsoft unveiled Direct3D 11 at the Gamefest 08 event in Seattle, with the major scheduled features including GPGPU support (DirectCompute), tessellation[29][30] support, and improved multi-threading support to assist video game developers in developing games that better utilize multi-core processors.[31] Direct3D 11 runs on Windows Vista and Windows 7. It will run on future Windows operating systems as well. Parts of the new API such as multi-threaded resource handling can be supported on Direct3D 9/10/10.1-class hardware. Hardware tessellation and Shader Model 5.0 require Direct3D 11 supporting hardware.[32] Microsoft has since released the Direct3D 11 Technical Preview.[33] Direct3D 11 is a strict superset of Direct3D 10.1 - all hardware and API features of version 10.1 are retained, and new features are added only when necessary for exposing new functionality.

Microsoft released the Final Platform Update for Windows Vista on October 27, 2009, which was 5 days after the initial release of Windows 7 (launched with Direct3D 11 as a base standard).

Compatibility

Various releases of Windows have included and supported various versions of DirectX, allowing newer versions of the operating system to continue running applications designed for earlier versions of DirectX until those versions can be gradually phased out in favor of newer APIs, drivers, and hardware.

APIs such as Direct3D and DirectSound need to interact with hardware, and they do this through a device driver. Hardware manufacturers have to write these drivers for a particular DirectX version's device driver interface (or DDI), and test each individual piece of hardware to make them DirectX compatible. Some hardware devices only have DirectX compatible drivers (in other words, one must install DirectX in order to use that hardware). Early versions of DirectX included an up-to-date library of all of the DirectX compatible drivers currently available. This practice was stopped however, in favor of the web-based Windows Update driver-update system, which allowed users to download only the drivers relevant to their hardware, rather than the entire library.

Prior to DirectX 10, DirectX runtime was designed to be backward compatible with older drivers, meaning that newer versions of the APIs were designed to interoperate with older drivers written against a previous version's DDI. The application programmer had to query the available hardware capabilities using a complex system of "cap bits" each tied to a particular hardware feature. For example, a game designed for and running on Direct3D 9 with a graphics adapter driver designed for Direct3D 6 would still work, albeit most likely with degraded functionality.

However, the Direct3D 10 runtime in Windows Vista cannot run on older hardware drivers due to the significantly updated DDI, which requires a unified feature set and abandons the use of "cap bits".

Direct3D 11 runtime introduces Direct3D 9, 10, and 10.1 "feature levels", compatibility modes which only allow the use of hardware features defined in the specified version of Direct3D. For Direct3D 9 hardware, there are three different feature levels, grouped by common capabilities of "low", "med" and "high-end" video cards; the runtime directly uses Direct3D 9 DDI provided in all WDDM drivers.

.NET Framework

In 2002 Microsoft released a version of DirectX compatible with the Microsoft .NET Framework, thus allowing programmers to take advantage of DirectX functionality from within .NET applications using compatible languages such as managed C++ or the use of the C# programming language. This API was known as "Managed DirectX" (or MDX for short), and claimed to operate at 98% of performance of the underlying native DirectX APIs. In December 2005, February 2006, April 2006, and August 2006, Microsoft released successive updates to this library, culminating in a beta version called Managed DirectX 2.0. While Managed DirectX 2.0 consolidated functionality that had previously been scattered over multiple assemblies into a single assembly, thus simplifying dependencies on it for software developers, development on this version has subsequently been discontinued, and it is no longer supported. The Managed DirectX 2.0 library expired on October 5, 2006.

During the GDC 2006 Microsoft presented the XNA Framework, a new managed version of DirectX (similar but not identical to Managed DirectX) that is intended to assist development of games by making it easier to integrate DirectX, High Level Shader Language (HLSL) and other tools in one package. It also supports the execution of managed code on the Xbox 360. The XNA Game Studio Express RTM was made available on December 11, 2006, as a free download for Windows XP. Unlike the DirectX runtime, Managed DirectX, XNA Framework or the Xbox 360 APIs (XInput, XACT etc.) have not shipped as part of Windows. Developers are expected to redistribute the runtime components along with their games or applications.

No Microsoft product including the latest XNA releases provides DirectX 10 support for the .NET Framework.

The other approach for DirectX in managed languages is to use third-party libraries like SlimDX for Direct3D, DirectInput (including Direct3D 10), Direct Show .NET for DirectShow subset or Windows API CodePack for .NET Framework which is an open source library from Microsoft.

Alternatives

There are alternatives to the DirectX family of APIs, with OpenGL having the most features. Examples of other APIs include SDL, Allegro, OpenMAX, OpenML, OpenAL, OpenCL, FMOD, etc. Many of these libraries are cross-platform or have open codebases.

There are also alternative implementations that aim to provide the same API, such as the one in Wine.

See also

- OpenGL

- Simple DirectMedia Layer

- Comparison of OpenGL and Direct3D

- Graphics Device Interface (GDI)

- Graphics pipeline

- DxDiag

- DirectX plugin

- ActiveX

- List of games with DirectX 10 support

- List of games with DirectX 11 support

References

- ↑ The meaning of Xbox; Microsoft.(Xbox 360) | Economist (US), The

- ↑ DirectX Help

- ↑ What is DCI?

- ↑ Craig Eisler's blog post about the frenzy to build DirectX 1 through 5 on craig.theeislers.com

- ↑ Jay Barnson (July 13, 2006). "Wildest Birthday Party EVER". http://rampantgames.com/blog/2006/07/wildest-birthday-party-ever.html.

- ↑ J. Allard, PC Pro Interview, April 2004

- ↑ DirectX SDK Release Notes on MSDN

- ↑ DirectX 9.0c Microsoft Official Download

- ↑ DirectX 9 (2010) update

- ↑ Direct link to last pure 32-bit DirectX 9.0c from December 13, 2004 & Direct link to first 64-bit capable DirectX 9.0c from February 9, 2005

- ↑ Last DirectX 9.0c for Windows 98/Me from December 13, 2006 & First DirectX 9.0c not for Windows 98 and Windows Me from February 13, 2007

- ↑ DirectX 9.0c February 2010

- ↑ DirectX End-User Runtimes (February 2006) Full Download which is the last version does not support VistaDirectX End-User Runtimes (April 2006) Full Download which has Vista on the support list

- ↑ DirectX End-User Runtimes (March 2009) which is the last version does not support Windows 7DirectX End-User Runtimes (August 2009) which has Windows 7 on the support list

- ↑ DirectX End-User Runtimes (June 2010)

- ↑ Microsoft upgrades Windows Vista with DirectX 11 (includes Server 2008, SP2 is required for both)DirectX 11 for Windows Vista SP2 Available for Download (includes Server 2008, SP2 is required for both)

- ↑ Chen, Raymond (2006). "Etymology and History". The Old New Thing (1st edition ed.). Pearson Education. p. 330. ISBN 0-321-44030-7.

- ↑ DirectX and Windows XP

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 David Craddock (March 2007). "Alex St John Interview, page 2". Shack News. http://www.shacknews.com/featuredarticle.x?id=283&page=2. Retrieved 2008-06-03.

- ↑ 3D Animation of SPACE FIGHTER by DIRECT ANIMATION

- ↑ Introducing the New Managed Direct3D Graphics API in the .NET Framework

- ↑ Microsoft.Xna.Framework.Graphics namespace

- ↑ DirectX Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ Download DirectX 10 for Windows XP TechMixer

- ↑ Chuck Walbourn (August 2009). "Graphics APIs in Windows". MSDN. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee417756.aspx. Retrieved 2009-10-03.

- ↑ "Microsoft Unleashes First Service Pack for Vista". PC Magazine. 2007-08-29. http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,1895,2177205,00.asp. Retrieved 2007-08-29.

- ↑ "Microsoft Presents DirectX 10.1 Details at SIGGRAPH". 2007-08-07. http://www.extremetech.com/article2/0,1558,2168429,00.asp?kc=ETRSS02129TX1K0000532. Retrieved 2007-08-27.

- ↑ "DirectX 10.1 Requires No New GPU". Windows Vista: The Complete Guide. 2008-03-05. http://xyzzy-links.blogspot.com/2007/08/directx-101-requires-no-new-gpu.html. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ "What's next for DirectX? A DirectX 11 overview - A DirectX 11 overview". Elite Bastards. September 1, 2008. http://www.elitebastards.com/cms/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=611&Itemid=29. Retrieved 2008-09-04.

- ↑ "DirectX 11: A look at what's coming". bit-tech.net. September 17, 2008. http://www.bit-tech.net/bits/2008/09/17/directx-11-a-look-at-what-s-coming/1.

- ↑ Windows 7 and D3D 11 release date

- ↑ Gamefest 2008 and the DirectX 11 announcement

- ↑ DirectX Software Development Kit

External links

- Microsoft's DirectX developer site

- The State of DirectX 10 - Image Quality & Performance

- DirectX at the Open Directory Project

- AMD talks about technical changes in DX11

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||